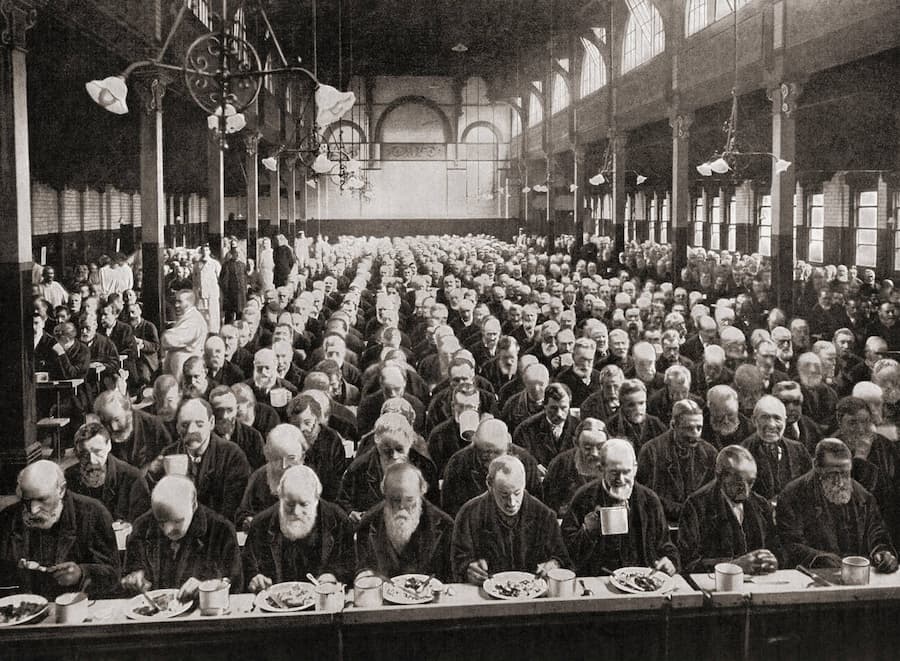

The year is 1890. The air is thick with the smell of damp stone and unwashed bodies. You stand in a long, silent line, your empty stomach a gnawing void. This isn’t a bustling restaurant or a cozy family kitchen. This is the St Pancras Workhouse, and it’s dinnertime.

The bell tolls, its sound a death knell for any lingering hope. You shuffle forward, a faceless shadow among a hundred others. The hall is cavernous, the only light coming from a few flickering gas lamps that cast long, grotesque shadows on the walls. The silence is deafening, broken only by the scrape of boots on the stone floor and the rhythmic thud of a ladle hitting a tin plate.

The Gruel: A Meal of Despair

Your turn arrives. A gaunt, hollow-eyed man stands behind a large pot, a grim-faced warden observing his every move. He scoops a watery, gray liquid onto your plate. This is your meal: gruel. It’s a thin, flavorless concoction of oats and water, meant to sustain life but offering no comfort. Sometimes, if you’re “lucky,” there might be a single, tough piece of meat, but it’s more likely to be a bone or gristle.

You retreat to a long, communal table, sitting shoulder to shoulder with others who share your fate. No one speaks. There are no thanks, no complaints, only the silent, desperate act of eating. The gruel is gone in a few spoonfuls, leaving you with a lingering taste of despair and a stomach that feels emptier than before.

The Scramble for Scraps

In this desolate place, every calorie is a treasure. Woe betide anyone who spills a drop. The silence is punctuated by the occasional gasp of a child whose gruel has been knocked over, followed by the swift, unmerciful strike of the warden’s cane. The desperation is palpable. On some nights, a single slice of stale bread is distributed, and you watch as the weakest are pushed aside by those whose hunger has turned them into beasts.

This wasn’t just a meal; it was a ritual of dehumanization. It was a stark reminder that you were a burden, a problem to be contained and managed. The meager portions weren’t just about saving money; they were a tool of control, a way to break the spirit of the inmates and ensure they never forgot their place.

The Aftermath: A Lingering Hunger

The meal is over as quickly as it began. The plates are collected, scraped clean by the very people who just finished eating, and you are ushered out of the hall. The hunger remains, a physical ache that will haunt your dreams. You are left with the cold reality of your situation, a feeling of utter insignificance in a world that has no use for you.

Dinnertime at the St Pancras Workhouse was a chilling tableau of Victorian society’s cruelty. It wasn’t about nourishment; it was about punishment, control, and the relentless breaking of the human spirit. It serves as a haunting reminder of a dark chapter in history, a time when poverty was treated not with empathy, but with a cold and brutal indifference.